16 May 2024 by Kathy Slater

Certified carbon and biodiversity projects aim to provide income for local communities in exchange for protecting or restoring important ecosystems. While ecosystems can be monitored throughout the duration of these projects to ensure that the climate and biodiversity goals of the project are being achieved, ecosystem service payments should also aim to look beyond the duration of the project and ensure permanent positive impacts (Grima et al., 2016; Le Tuyet et al., 2024). This issue of permanence is difficult to achieve if communities simply receive cash payments for protecting or restoring ecosystems are the underlying issues that are threatening to or already have degraded the ecosystem are not addressed (Jaureguiberry et al., 2022). What happens when the ecosystem services payments stop? If, however, income generated from carbon and biodiversity credits is invested in sustainable economic development with the communities that reside in the project ecosystems, such that implemented changes are both more sustainable and more profitable, then there is a much higher likelihood of project permanence.

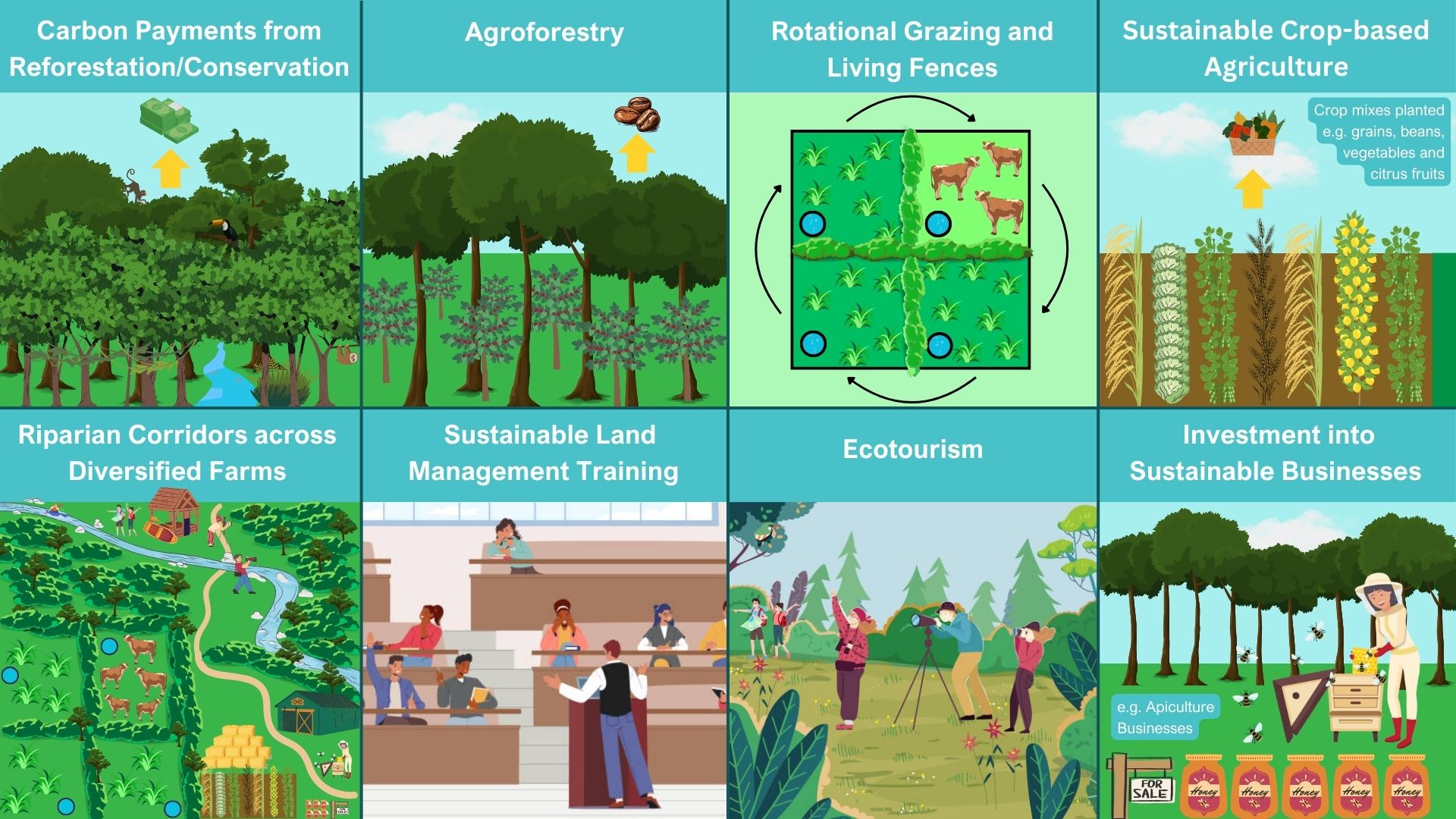

The rePLANET approach to forest ecosystem restoration is to work with local communities to increase forest cover, maximize habitat connectivity, and increase sustainability and profitability of diversified agricultural landscapes all within a complex forest-farm matrix. Riparian forest corridors can be planted to connect existing forest fragments and protect water sources (Langhans et al., 2022). Forested areas can progress into designated areas for agroforestry, silvopastoral methods including living fences, scattered shade trees and rotational grazing can be implemented on remaining cattle pasture, and mixed-crop agriculture with no burning or chemicals used can be implemented for both subsistence and income. The methods are not only proven to improve sustainability of farming (Foster et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2017; Aryal et al., 2022), but once the interventions on farms are implemented, these methods also reduce farming costs and increase profitability (Teague, 2018; Valenzuela et al., 2022). In addition, communities can be trained in sustainable farming techniques and business management and investment can be made in new sustainable income streams such as honey production or wildlife orientated ecotourism in existing forested areas, see figure 1.

Figure 1: Farms involved in rePLANET projects will receive funding for ecosystem restoration, sustainable land management practices and sustainable businesses and livelihood development, promoting project intervention permanence.

The exact combination of sustainable land management and new income streams implemented in each project can be determined by the characteristics of the forest ecosystem and then needs and interests of the communities. Such extensive investment in community livelihoods can be costly, but this can be offset by certification of multiple project activities for carbon and biodiversity credits rather than just certification of reforestation (Aryal et al., 2022). All relevant carbon pools for each project activity (e.g. reforestation, agroforestry, rotational grazing) can be quantified and monitored throughout the duration of the project to generate certified carbon credits, support the climate mitigation aims of the project and increase the income generated for investment in community livelihoods. The same can be achieved for the biodiversity protection or biodiversity uplift associated with each project activity where quantified multi-taxa biodiversity data collected at baseline and throughout the duration of the project can be used to document the biodiversity benefits of each project activity, provide evidence to support the biodiversity claims of the project and maximize the income for communities.

This multifaceted investment in sustainable livelihoods as opposed to cash payments to restore or protect ecosystems can ensure that all genders and age groups can participate and benefit from the project, and can genuinely remove the constant need to clear more forest to make way for agriculture, which is the biggest threat to forest ecosystems and their biodiversity (Dudley & Alexander, 2017).

References:

Aryal, D. R., Morales-Ruiz, D. E., López-Cruz, S., Tondopó-Marroquín, C. N., Lara-Nucamendi, A., Jiménez-Trujillo, J. A., Pérez-Sánchez, E., Betanzos-Simon, J. E., Casasola-Coto, F., Martínez-Salinas, A., Sepúlveda-López, C. J., Ramírez-Díaz, R., la O Arias, M. A., Guevara-Hernández, F., Pinto-Ruiz, R., & Ibrahim, M. (2022). Silvopastoral systems and remnant forests enhance carbon storage in livestock-dominated landscapes in Mexico. Scientific Reports 2022 12:1, 12(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21089-4

Foster, B. C., Wang, D., Keeton, W. S., & Ashton, M. S. (2010). Implementing Sustainable Forest Management Using Six Concepts in an Adaptive Management Framework. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 29(1), 79–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10549810903463494

Grima, N., Singh, S. J., Smetschka, B., & Ringhofer, L. (2016). Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) in Latin America: Analysing the performance of 40 case studies. Ecosystem Services, 17, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOSER.2015.11.010

Jaureguiberry, P., Titeux, N., Wiemers, M., Bowler, D. E., Coscieme, L., Golden, A. S., Guerra, C. A., Jacob, U., Takahashi, Y., Settele, J., Díaz, S., Molnár, Z., & Purvis, A. (2022). The direct drivers of recent global anthropogenic biodiversity loss. Science Advances, 8(45). https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIADV.ABM9982

Langhans, K. E., Schmitt, R. J. P., Chaplin-Kramer, R., Anderson, C. B., Vargas Bolaños, C., Vargas Cabezas, F., Dirzo, R., Goldstein, J. A., Horangic, T., Miller Granados, C., Powell, T. M., Smith, J. R., Alvarado Quesada, I., Umaña Quesada, A., Monge Vargas, R., Wolny, S., & Daily, G. C. (2022). Modeling multiple ecosystem services and beneficiaries of riparian reforestation in Costa Rica. Ecosystem Services, 57, 101470. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOSER.2022.101470

Le Tuyet, A. T., Vodden, K., Wu, J., Bullock, R., & Sabau, G. (2024). Payments for ecosystem services programs: A global review of contributions towards sustainability. Heliyon, 10(1), e22361. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2023.E22361

Teague, W. R. (2018). FORAGES AND PASTURES SYMPOSIUM: COVER CROPS IN LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION: WHOLE-SYSTEM APPROACH: Managing grazing to restore soil health and farm livelihoods. Journal of Animal Science, 96(4), 1519–1530. https://doi.org/10.1093/JAS/SKX060

Valenzuela Que, F. G., Villanueva-López, G., Alcudia-Aguilar, A., Medrano-Pérez, O. R., Cámara-Cabrales, L., Martínez-Zurimendi, P., Casanova-Lugo, F., & Aryal, D. R. (2022). Silvopastoral systems improve carbon stocks at livestock ranches in Tabasco, Mexico. Soil Use and Management, 38(2), 1237–1249. https://doi.org/10.1111/SUM.12799

Williams, D. R., Alvarado, F., Rhys, |, Green, E., Manica, A., ben Phalan, |, Balmford, A., Ia, E., Xalapa, A. C., Correspondence, D. R., & Williams, B. (2017). Land-use strategies to balance livestock production, biodiversity conservation and carbon storage in Yucatán, Mexico. Global Change Biology, 23(12), 5260–5272. https://doi.org/10.1111/GCB.13791